| I was caught, like a fly in a spider web, in a trap of my own

devising. I was determined to escape. So of course, I decided to build a

boat. Let me explain. At age 48, I had a good job and many

responsibilities. Too many responsibilities and I longed to get away at

times, even if just for a few hours, to claim a life. Somehow, sailing a

boat came to be the focus of that longing, the vehicle for a temporary

escape from the pressures of the rat race, a magic carpet on which to ride

the waters of Puget Sound.

I resisted actually buying a sailboat for a number of reasons. First

there was the expense, a commitment not only to paying for the boat, but

also slip fees and maintenance. It seemed an expensive proposition. There

was also the fact that whenever I visited the local marinas, I noticed

that most boats never left the dock. I just wasnít sure I wanted to pay

for moorage and have my boat sit there unused. The boat owners I knew had

difficulty getting family and friends to come along on a sail. Whatever

the causes, so many beautiful sailboats were relegated to

on-the-water-condo status. I was cautious and I needed to learn more.

So I joined a sailing club in Seattle. There I learned to sail on

bigger boats, typically 30 to 36 foot Catalinas. But these boats seemed a

bit like seagoing Winnebagos to me. And sailing in Shilshole Bay struck me

as redundant. Over time I became a convert to the small is beautiful

movement. I wanted a small boat that could be trailered around to various

spots and sailed on thin water, away from the hustle and bustle of big

marinas and busy waterways. But I still wasnít ready to buy a boat.

Thatís when I came across the Instant Boat books. I read and re-read

these books. This seemed to be the solution to my problem! I would build a

simple and elegant boat that I could sail around my local waters or take

anywhere to explore new bodies of water. Perfect! Except for one nagging

problem. I had no tools and absolutely no skills as a builder of anything.

Now I know some first time boat builders are humble about their skills.

This was not the case with me. Iím not exaggerating my lack of ability. I

measure once and cut twice every time. No concept is so simple I canít

complicate it. I cannot cut straight. This is not an exaggeration. I am

spatially challenged. I canít follow plans. And yet I became determined to

build a boat. I felt I was being directed by some primal force. Building a

boat myself came to symbolize independence and self-sufficiency. Like

thousands of men and women before me, through long history, I would build

my boat and sail away to distant shores!

Who would have guessed that the next step would be so challenging,

namely, selecting a boat to build? I have to admit I spent many hours in

sweet agony trying to decide which instant boat to construct. For whatever

reason, I eliminated the tiny boats. At the time I probably thought they

were not real boats and the building of one would seem more like building

a model or a toy. Looking back, I think I was wrong. Building a Brick

might have been the best choice for a fast learning experience. But at the

time, I wanted to build something more substantial. Finally, it came down

to Zephyr or Surf or Windsprint. I think I ended up choosing Windsprint

because of the pictures and description of it in the New Instant Boats

book. Whatever the reasons, I chose Windsprint and ordered the plans.

When the plans arrived, I got my first shock. All that was included

was a bigger picture of the plans than was in the book and single sheet of

numbered instructions, clearly meant for people who already knew what they

were doing! I needed something more basic. Instead of plans that stated,

for example, ďCut sides out from plywood according to plan,Ē I needed

advice on how to cut a straight-line for eight feet. This idea of building

a boat on my own was going to be far more challenging than I even

imagined.

First, I went to a local lumberyard and hardware store where I could

buy some marine grade plywood. I had the lumberman slice the sheets into

the long panels, which would become the hull. These were the first cuts to

be made to form my Windsprint.

The next impossible task, as I recall, was to join the various

pieces of plywood with butt blocks. The concept is to join two pieces of

plywood at the edges by overlapping a small piece of plywood over the

joint, gluing the pieces and holding that together until the glue dries. I

believe this is easier if you have a wooden floor into which you can pound

nails or drive screws through the whole joint and leave it until it dries.

Then you can remove the screws and fill in the holes or clinch over the

nails or even grind them off. Somehow I got the panels joined. Still, as

other home boat builders have opined, butt joints are a necessary evil.

Speaking of glue, I used Weldwood as recommended by Payson in

Instant Boats, but I also used epoxy. Unfortunately, it turned out Iím

allergic to epoxy. My face swelled up to the point of almost closing my

eyes. I looked like Quasimoto the boat builder. This discovery has

impacted all my boat building, since I try to avoid epoxy at all costs.

Back to building Windsprint, the next step was to slice two by fours into

gunwales and chines. As was customary in my boat building approach, I did

this all wrong and with much greater difficulty than necessary. First, I

borrowed a table saw. Then I set the blade at the correct angle and

proceeded to push the lumber through, quickly grinding to a halt because

the long pieces kept binding and I had no roller stands (honestly, at the

time I didnít know from roller stands). Instead, I enlisted the help of

neighbors who acted as roller stands and eventually I got out some useable

pieces. Today I would simply use my circular saw, set to the correct angle

and depth, attach the guide and quickly and easily rip long pieces out of

stock. But this is now and that was then.

Molds, or temporary bulkheads were next. I drew these on plywood,

cut them out as best I could and then added the stock. I donít know if I

got the bevels right. It remains a mystery to me which side of the bevel

the plywood goes, or whether the plywood edge needs to be beveled. The

funny thing about the molds I made for my Windsprint is I used those

bronze ring nails to fasten the plywood to the stock and I never could get

them apart. They were the sturdiest part of the construction! Next, the

directions say to ďstand sides on edge bottom up and tack mid mold in

place.Ē This step is fraught with problems for the neophyte. I had no idea

what tack meant. Or how to hold the sides upright along with the mold and

attach them. Finally I settled on screwing the sides to the mold using

drywall screws after first drilling pilot holes. It worked. Ditto for the

two other molds.

Windsprint is a double ender and requires both a stem and stern

piece, each piece angled to accommodate the sides of the boat where they

join at each end. There are no directions for how to do this. I think you

just look at the plan and come up with something. Here is what I came up

with: I drew the shape of the stem piece on the edge of a suitable two by

four and then laid that up on my borrowed table saw and adjusted the blade

to copy the angle drawn on the piece. This was a bold step because, if you

look at the plans in ďBuild the New Instant BoatsĒ youíll find that both

pieces are supposed to be one and five eighth inches deep. Uh, that would

be one-eighth inches deeper than a two by four. All I can tell you is my

boat floats, apparently I could get by with stem and stern pieces one

eighth of an inch undersized.

For reasons totally unclear to me, I had no problem whatsoever

bringing the ends together then gluing and screwing them fast. The hull

came out straight with no twists that I could tell. Suddenly, my work

looked like a boat!

The chine logs did not go on as easily. For one thing, I discovered

I did not own enough clamps to hold the chines in place. I ended up

screwing the chines to the sides, later removing the screws and filling

the holes. As I tell my friends and neighbors who ask about my boat

building experience, itís all about clamps. No matter what I go to the

hardware store for, I pick up a clamp.

I used half-inch marine plywood for the bottom of my Windsprint even

though the plans call for quarter inch. I did this on the advice of

another builder, John Bell, and Iím glad I did. It has made for a pretty

sturdy boat. The bottom went on fairly easily. I ground the overhang of

the bottom down with a coarse sandpaper disk on my drill. Turned out real

nice. I believe I had a neighbor come over and paint the edges of the

plywood pieces with epoxy. I know he painted my dagger board and rudder

pieces with epoxy. I hoped this would make the plywood less susceptible to

absorbing water and rotting out.

I turned the boat over and started putting on gunwales. What a

thankless job! I only installed two courses, although the plans called for

three. By the way, how are you supposed to finish the gunwales and chines,

at both ends of the boat? The instructions are rather silent on this. They

say, ďTurn boat right side up and put on rails.Ē I cut the ends off at an

angle and planed them down to almost blend in with the sides. I had some

difficulty getting the ends of the gunwale or chine log to curve in at the

stem and stern. Since then, I have seen examples of gunwales built by

laminating much thinner pieces of wood together. You can do this if you

have enough clamps. This will allow you to secure the pieces snugly to the

curve and then trim them off square at the end before shaping. I know,

most of you are saying, ďWhy didnít you do that in the first place?Ē

It was at this point that I started to modify Windsprint a little. I

decided to deck over the fore and aft ends of the boat. I did this because

I so admire the look of a decked over boat and, I thought to myself, the

result would be a drier, more capsize resistant boat. That turned out to

be not true. I wonít go into what it took to do this, but you may be able

to see from the pictures something of how I did it. Decking over the boat

changed the mast partners configuration and the dagger board case.

I never did understand from the plans how to build the case. As it

was, I simply built a box the correct size and mounted it to the bottom of

the boat and to the side rail. I epoxied this in, which cost me some

allergic reaction, but it had to be done. Cutting a hole in the bottom of

the boat was traumatic for me. Think about it. As a measure once, cut

twice kind of shipwright, I had a better than even chance of ruining the

whole project right there. Of course I measured the thing about fifty

times, drew around the outside of the case and measured off the inside

dimensions then drilled holes at either end and cut out the slot with my

jig saw. It came out perfect! To this day the dagger board case has not

sprung a leak.

Next came the rudder and dagger board. Iím happy to report these

were fairly easy to do. One thing that helped was the fact I used

half-inch marine plywood left over from the bottom, so I didnít have to

put two halves together. I again used a course sandpaper disk mounted to

my drill to shape the edges of both the dagger board and the rudder. This

worked well and went pretty quick. I designed in a handle on the dagger

board that works real well and the rudder has some strings on it that I

use to raise it up or keep it down. The tiller is a work of art. Well if

not art, it looks and feels nice. Of course it isnít curved but it is

stained and varnished. It feels good in my hand.

I never did figure out Payson eyes to attach the rudder to the

sternpost, so I used eye screws and bolts. It seems to work.

So, all I had left to do was the mast, paint the boat, add a sail,

oarlocks and oars. Ah, the mast. Unfortunately, I have never conquered

this part of boat building. Not to this day and not for lack of trying

mind you. My first attempt was to shape a mast out of a 4x4. I found a

nice piece at the lumberyard and went at it with my plane. Now this was a

laborious process, but it turned out to be a labor of love. The shavings

were to me a thing of beauty. The texture and grain of the wood mast

itself, as it took shape, seemed to come alive. But even as I worked on

it, the mast began to warp. To this day it lies out in my backyard next to

the fence, looking like a giant pool cue gone bad. I think someday Iíll be

able to use one end as a bowsprit.

My next mast came from a dead fir tree harvested out of the

greenbelt behind my house. In truth, I have a dozen masts out there, still

planted in the ground but dead from a terrible ice storm we had a few

years ago which killed off many of the young fir trees around here. They

literally broke off at the top from the weight of the ice. Anyway, I

debarked this tree, planed it down and Iíve actually used it. It works

pretty well, but it has some cracks and worm holes and knots where small

branches once stuck out. I never really finished this mast smooth or

treated it with any preservative. I always planned to build a mast and so

just kept this one handy. My next attempt at mast building came from an

idea that someone promoted on the Bolger e-mail group. This involved using

PVC pipe filled with wood. This actually worked okay, but produced a heavy

mast all of one size from top to bottom. When I later converted my

Windsprint to a lateen sail, I cut this mast down to ten feet and it

worked real well. My next attempt at a mast should have worked. I had some

nice cedar 2x4ís which I cut down to three inches and then glued together

with the grain running in opposite directions to impede warping. I donít

know what I did wrong, but that glued together mast blank is crooked. I

never even went the next step with it. The funny thing is, I just came

into possession of a mast someone else made for a Bolger boat. It is from

a single piece of wood, it is nicely tapered and light. Along with it I

received a sprit and a Teal type sail. It has inspired me to build yet

another boat. But that is a story for another time. The point is, seeing

that mast close up, I know I could make one myself. But I have a goal in

mind: to build a hollow birdís mouth mast. What an elegant solution for a

lightweight wooden mast!

I ordered a sail from someone back east. It is a beautiful, crisp

Dacron sail. Iíve got to tell you though, it is huge. Many of you have

seen pictures of Windsprints on the Internet and you see that big balanced

lugsail suspended from the yard and you have to wonder, how does that boat

hold up all that sail in a breeze? Well, forget about that for a moment.

The sail is so big is takes up the whole cockpit when you drop it. Between

the sail, the boom and the yard, it is very challenging to find room to

row the boat.

For the boom and yard I went with fir one and half by one and a

half. I havenít trimmed them or treated them in any way, which is

something I should get around to doing someday. But I do have a clever way

to attach the sail to the spars. Perhaps I got this idea from someone

else, I honestly donít remember, but I use wire ties. They work perfectly.

Cinch it up to just the right tension and trim it off. Perfect. I havenít

had one break yet. They are inexpensive, easy to remove and of course,

individual sail ties have the advantage of being individual. If one does

break the whole sail does not come unattached from the spar.

Finally, I painted the boat. Now I like the term ďwork boat finish.Ē

I use this term to excuse the fact that my boat does not have a museum

quality finish. I didnít enjoy sanding all that much. By the way, does

plywood sand down to a smooth finish, or do you apply ten coats of primer,

sanding between each coat? No matter for my boat. I put latex primer on it

then painted it with latex gloss enamel. One hundred percent acrylic.

Brushed on a couple of coats. I let it dry for a few weeks. This would

have driven me nuts, waiting to launch while the paint dried thoroughly,

but it took me a few weeks to find and buy a trailer. Finally, launch day

came.

How can I describe the mixture of emotions I felt as the boat I

built slid off the trailer and into the water? Excitement, pride, fear,

anxiety, uncertainty. Would it float? Would it tip over? To tell you the

truth, I donít remember how I rigged the boat for sailing. I must have

gotten the sail up prior to pushing out into the lake. I do remember the

lake was mirror flat. There was literally no wind. My neighbor was with me

and we didnít have much time and we were using his truck, so the initial

sail of my Windsprint was very limited. But there was one single puff of

wind. Just that one puff lifted my boat and moved it. It sailed for a

moment, easily, picking up momentum from just that little catís paw of

wind. It was like a down payment on all my hard work. My boat was a good

design and it responded to the elements! On other days I would learn a lot

more about my boat and how to sail it. But just that one little puff was

memorable.

I left the sail up and my neighbor rowed while I steered the boat

back to shore. We put it back on the trailer and went home. On another

occasion my neighbor videotaped the boat sailing on the lake at sunset. It

is a beautiful tape. It shows the boat tacking back and forth gracefully,

here and there picking up a puff and accelerating. All around the boat are

people whizzing by on jet skis. But the vision of a handmade wooden boat,

powered by sail, is strong enough to block out all the noise and exhaust

fumes and crisscrossing wakes, creating an almost transcendent picture of

wood, wind and water.

I have since taken Windsprint out for many hours of sailing, mostly

on the south Puget Sound. These are protected waters, with lots of room

for a daysailer. There are out of the way places where the water is thin

and motorized boats donít come around much. My Windsprint doesnít need

much wind to move her. A modest breeze makes for some very relaxed

sailing. It is a comfortable boat with lots on room on the bottom for

lolling around. One day I was able to lie back in the boat and watch the

sky pass overhead. Some days I would tack the boat back and forth just to

get out of the shade of the sail and catch a few rays of the sun.

Windsprint is a flat-bottomed boat so it pounds against waves and chop,

but heeling to about 15 degrees minimizes the pounding. At that point the

boat slices through the water quite nicely. The boat launches and

retrieves with no problems and it wasnít too long before I got pretty good

at single-handedly launching the boat from shore, dropping the dagger

board, putting down the rudder and trimming sail in time to steer the boat

away from shore. Of course, this was at the lake or at a put in on the

Sound where there is no dock. From the dock, greater challenges would

arise, like maneuvering around other boats and having the wind blocked by

boats at moorage.

These days of sailing in light breezes were great for getting to

know the boat and really learning how to sail. But not all was perfect. I

learned right away that when there were not enough breezes to sail the

boat, it was almost impossible to lower the sail and row home. There is

just nowhere to put the sail, the boom and the yard. I also suspected that

Windsprint would be very difficult to bail out and re-enter in case of a

capsize. Other Windsprint owners cautioned that it is not if you capsize,

but when you do so. I later learned firsthand just how difficult this boat

is to handle after a dumping.

Because of these concerns, I decided to change Windsprintís sail

plan to a more conservative one and I tried to beef up its flotation so it

would be easier to recover from a dunking. I chose to make a lateen sail

for my Windsprint based the dimensions of the Sunfish sail plan. I made

the sail out of polytarp. I cut the sides cambered to about three inches,

which built in some some fullness and draft and I got a very weatherly

sail out it. I ran it up on a shortened mast and it worked very well. The

lateen sail was about 75 square feet compared to the original 115 or so

square feet of the balanced lug sail Windsprint was designed for. But this

did not really solve my problem of being able to drop sail and row home or

to shore. Even the lateen sail, though smaller in size, has a boom and a

yard and canít be cinched up while on the mast.

One thing I should mention right now about Windsprint. It is a great

rowing boat. It is easily driven and moves quickly and is efficiently. I

think pulling boats are measured against a benchmark of how far they will

glide on a single pull in calm water. I believe Windsprint would measure

up pretty well. So it would be desirable to be able to conveniently row

the boat at will, but that requires a solution for stowing the sail and

spars.

I think those of us who like to build these small unballasted boats

should concentrate some of our energy and creativity on inventing a sail

plan that is easily reefed and furled. I would think a good starting place

would be the patented system used on the Escape sailboats. These sail

plans employ a separate mast and boom and allow the sail to be furled

using a single line.

Early this spring I took my boat down to the boat launch and

prepared to go for a little sail. The wind was blowing pretty good, harder

than I had ever sailed in before but I thought it would be okay. In fact,

I never got sailing. I lost control of the boat at the dock and tipped it

over. To my dismay, it filled up completely with water. I had hoped that

the boat, if dumped, would rest on its side, but no way. Perhaps that is

because it is a double ender. The boat actually turned completely turtle.

From the dock I was able to turn the boat right side up and start the

bailing process. If I had been out in the water I donít think I could have

done it. This unhappy event got me to thinking. To fully enjoy sailing, I

need more stability and peace of mind. I canít be worrying about dumping

the boat because the mainsheet gets hung up or sudden gust knocks me over.

I DECIDE TO CONVERT WINDSPRINT

INTO A TRIMARAN

Why should I convert my boat to a trimaran? I am now convinced that

a better question is, ďWhy arenít all boats trimarans?Ē I think the debate

about monohull and multihulls is a little like the use of chop sticks

versus a fork at a Chinese restaurant. Clearly, a fork is a more efficient

food delivery device, but chopsticks are traditional. Likewise, a trihull

is a more efficient form for supporting a sailing rig, but monohulls enjoy

the weight of tradition. Big monohulls, boasting large sail plans, are

ballasted to offset the force of the wind on the sails and prevent

knockdown, or worse, capsize. A capsized ballasted boat, which fills up

with water, sinks. Smaller, non-ballasted boats, such as my Windsprint,

depend on human ballast and a fast release of the sheet in a gust to

prevent capsizes. A boat like Windsprint does not sink when capsized, but

it does fill up with water, and becomes very difficult to bail out and

reenter.

Trimarans are faster than monohulls. This is because they can

support more sail area with less weight in the boat, and keep that area up

in stiffer breezes. A trimaran is a more stable platform to fish from, to

swim from and it is easier to reenter the boat from the water. So what are

the downsides to a tri? Well, you have to build three hulls instead of

one. Perhaps you canít point as well. They are more challenging to trailer

than a monohull.

But I have to tell you this debate seemed pointless to me once I

experienced a small trimaran called the Windrider. These boats are like a

kayak with floats. I rented one out of Port Townsend, Wa. The main hull is

about 16 feet long and the wingspread is eleven feet. The floats are wave

piercing but other than that I donít know too much about their shape. A

single sail of less than 100 sq. feet powers the boat. You sit in the boat

facing forward and use foot pedals to control the rudder. The mainsheet is

right in front of you rigged through a rotating fair lead and clam cleat.

The sail can be rolled up onto the mast. As soon as I got the boat onto

the water I was amazed at the feeling of stability and lightness afloat.

It was as if the boat was barely touching the water! The acceleration was

exhilarating. I knew right away this was the way to sail for me. Speed. No

worries. One is afforded the opportunity to take pictures or have a cup of

coffee, relax and enjoy the view. No impediments to cruising around in

thin water. You have the ability to beach the boat. The only drawbacks to

this boat are the lack of room for a passenger, the boat is made out of

plastic and it is a little ugly.

I knew right away I had to try and convert my Windsprint to a

trimaran. If it worked, I would have all the benefits of my Windsprint,

that is, a roomy cockpit, nice lines, light weight and wooden construction

plus the benefits of a tri, that is, stability and speed. Additional

advantages would be the ability to easily add a small outboard or electric

motor to the boat by mounting it on a connecting beam and I would be able

to drop sail and stow it and the spars outside of the main hull. I would

also have a small boat that I could stand in. This would allow for all

kinds of things you canít do or do as easily on Windsprint as originally

designed.

Notice that I am confident that Windsprint as a trimaran will not

capsize. I think that confidence is justified for good reasons. First, I

am not planning on adding sail area nor will I be using a spinnaker. I do

not plan on going out to sea or anywhere that Iím likely to get

significant wave action. The floats will be sealed and fairly voluminous.

It will take a typhoon, I think, to knock this boat over or powerful wind

and wave action combined to ďtrip it.Ē

Let me walk you through the design issues. What size and shape

should the floats be? What building process would I use? How would I

attach the floats to the main hull? Iím assuming that the rudder I already

have will be adequate to steer the boat. I am also assuming that the

dagger board is adequate as designed, although it would be easy to make

the board longer if necessary.

Since Windsprint is 16 feet long, I decided to make the amas 12 feet

long. No science here at all. Just seems like enough. I made them a foot

square at the midsection, tapered to a point at both ends. The top is flat

and the bottom is radically rockered. In other words, I am using square

boat principles here. I realize that most catamarans are vee shaped on the

bottom, but the Aqua Cat is, according to its marketing materials, flat

bottomed. So I donít think the form is problematic. I made the floats

ďinstant boatĒ style with exterior chine logs and gunwales.

I used quarter inch luan plywood for top, bottom and sides. To get

all the measurements, I drew the floats on two pieces of plywood laid down

end to end and drew the bottom. That gave me the angles for the stem and

stern pieces. Then I drew out a side by going a foot high then marking off

to six inches at either end. Halfway from each end to the middle I marked

off nine inches. Then I drove in some nails at those points and used a

batten to capture a fair curve. Then I cut out the first pieces and used

them as patterns for all the others. After cutting out all the pieces and

butt blocking them (I did no better this time than last time on this), I

then cut my stem and stern pieces on my table saw and attached them to one

panel. Next, I attached stock to the sides where the molds would be, In

essence, I just attached strips of wood a quarter inch apart where the

mold would go. When I assembled the sides I just slipped in the molds, cut

out from plywood, in the slots and drew the ends of the sides together.

Then I glued and clamped the ends together, but remember I already had the

stem and stern pieces attached on one side. Next I attached the chines and

gunwales to the sides. I used an air powered staple gun to do this ala

Greg Carlson. To get the chine log to take the curve, I kerfed it every 12

inches. This worked real well although it was a slight pain later on to

fill in the cracks with Bondo. Then it was just a matter of tracing the

bottom and tops, cutting them out, and butt blocking and attaching to the

boat. I must say having done all this once before made it much easier this

time around.

With the amas structurally complete, it was time to figure out how

to attach them to the main hull. I cut out a five-inch hole at both ends

of both floats to give me access to put in bolts, which is my first choice

for how to attach the beams to the amas. While Iím testing all this, Iíll

just put duct tape over the openings. Once Iím satisfied with how to

attach the floats to the beams, Iíll figure out some kind of hatch covers.

Speaking of the beams, Iím going to try 2x4ís. The total beam of the

boat is just 8 feet. The distance between the main hull and the float is

about 30Ē so there is a chance the beam can take the leverage. But it

wonít surprise me if a beam cracks at the point where it is bolted through

to the main hull. If that happens Iím going to look for a way to

permanently mount metal tubing of some kind on the main hull and on the

floats, then go with a connecting tube with a bolt through it at each end.

Because Iím not an engineer or a boat designer, I have some concerns

based on my ignorance of multihull design and construction. For example,

will there be a problem driving the hulls through the water? Will tacking

be problematic? Perhaps Iíll only be able to jibe. How far off the wind

will I have to sail? Because there is so much buoyancy in the floats, I

donít think they will get driven under, so all the force will either

translate to forward motion or the mast will snap off or the beams will

snap. These questions will have to wait for sea trials to get answered.

At last, it is Memorial Day weekend, 2002. I have finished the

conversion. Windsprint is now a trimaran! I lashed the akas to the main

hull and bolted them to the amas. The boat still fits on my trailer. I

took it down to nearby Black Lake and dropped her in the water with the

sail up. I readied the daggerboard, made sure the main sheet was not

fouled and pushed off. I picked up a tiny breeze coming in from the port

side and fell off a little, dropped the dagger board, pulled down on the

string that lowers the rudder and pulled in the sail. Basic beach cat

sailing, I think. Everything was going pretty good when I ran out of wind.

Turned out to be the calm before the storm, literally. A storm was coming

in from the west over hills surrounding the lake. The breeze freshened and

my new trimaran took off. Perfectly flat sailing with the whole sail up

and I was just boiling through the water. But I could tell it was

straining the boat. I headed for shore before the full storm arrived. Good

thing I did.

When I got the boat home I noticed that some separation had occurred

at the joint between the deck and gunwale on the port ama. I have no idea

what caused it. But, as I have suspected all along, the attachment of the

amas to the akas and the main hull is the most vulnerable spot on this

boat. Here is how I fixed it. First, I pried open the cracks and poured in

some glue. Next, I screwed down the deck into the gunwale. I covered it

all over with bondo and paint. I now attach the akas to the amas by

lashing, similar to what Iíve done with attaching the akas to the main

hull. This puts all the pressure on the gunwales of the ama instead of on

the deck.

A few more observations about how the boat acted on the water. The

wake from other boats is about the only source of waves on this small

lake. I was concerned that the wave action on the three hulls would be

problematic. In practice the main hull pounds just as if always does, but

the amas, because they are so narrow, seem to fair better. My other big

concern was that the akas would simply snap in two. This does not seem to

be the case, the akas held up just fine. I wasnít sure how maneuverable

the boat would be, but I found I could tack quite easily in about 100

degrees. The original blades seem to be plenty to steer the boat and keep

her way.

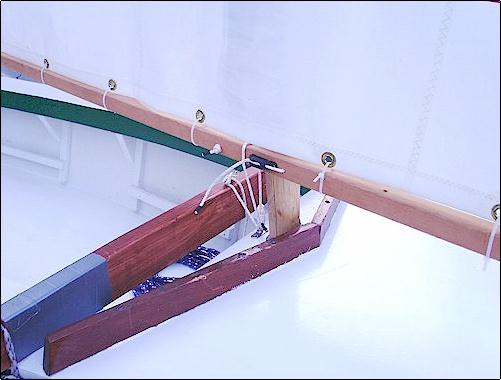

Here a few photos of the rigging details. The boom is held in place

next to the mast with a parrel, or line which I run to jam cleat. This

prevents the boom from pumping back and forth under in a breeze and also

keeps the sail from flying around when you first raise it. You can also

see a vang of sorts, which allows you to tension the luff of the sail

which is critical to achieving correct sail shape. I tie to pad eye

mounted on the deck just behind the mast, then loop over the boom, go back

through the pad eye and finally tie off to a cleat mounted on the aka.

Because the boat is now so stable, I will probably experiment with

different seating arrangements as alternatives to just lounging on the

floor of the boat. I also think an electric trolling motor mounted on the

aka would be the perfect auxiliary.

So Iím ready to do some real sailing in the Puget Sound this summer.

Hope you enjoyed the article. Please feel free to correspond to

Teakdeck@aol.com.

|