Building

a small gaff-rigged yawl, we needed lots of blocks. I was able to find

good ones, or cheap ones. Cost was an incentive, but the 'plasticy' look

of the commercial products was as big a factor for me. Having built the

boat, made the spars and sewn the sails, buying rigging didn't feel right.

Fortunately I'm not yet crazy enough to make my own rope. Building

a small gaff-rigged yawl, we needed lots of blocks. I was able to find

good ones, or cheap ones. Cost was an incentive, but the 'plasticy' look

of the commercial products was as big a factor for me. Having built the

boat, made the spars and sewn the sails, buying rigging didn't feel right.

Fortunately I'm not yet crazy enough to make my own rope.

Rope stropped blocks have very few metal parts; they can be made and

repaired with hand tools. They work, and for me, they just look right.

Four

components make up the basic block; a pulley or 'sheave' for the rope to

run over, an axle or 'pin' for the sheave to turn on, a wooden body or

'shell', and a 'strop' - generally a grommet - an (almost) endless rope

loop to wrap around the whole, providing an attachment point. The wooden

shell can be carved out of a solid lump of wood (a 'mortised' block) or

assembled from smaller bits of timber (a 'made' block). These are made

blocks. Traditionally, made blocks have the parts of their shells both

glued and riveted together. With modern adhesives, a made block should be

as strong as a mortised block. Rivets optional.... Four

components make up the basic block; a pulley or 'sheave' for the rope to

run over, an axle or 'pin' for the sheave to turn on, a wooden body or

'shell', and a 'strop' - generally a grommet - an (almost) endless rope

loop to wrap around the whole, providing an attachment point. The wooden

shell can be carved out of a solid lump of wood (a 'mortised' block) or

assembled from smaller bits of timber (a 'made' block). These are made

blocks. Traditionally, made blocks have the parts of their shells both

glued and riveted together. With modern adhesives, a made block should be

as strong as a mortised block. Rivets optional....

Materials:

Shell: Ideally, the wood for block-making should be light,

tough, durable and easily obtained - look around and see what's available

locally. The

USDA gives online information on the properties of all sorts of wood.

Mail order suppliers can provide small pieces of tropical hardwood stock

at moderate cost. The examples here are Canary wood (Centrolobium) and

Cocobolo, a Rosewood relative, both from

Lee Valley. Elm was traditionally used for block shells, since its

interlocking grain made it resistant to splitting.

Sheave: UHMW (Ultra High Molecular Weight) polyethylene is

soft enough to be worked with wood working tools, self lubricating, and

impervious to moisture. It can be obtained in small quantities from wood

working suppliers - again mine came from

Lee Valley. Alternatively, check under Plastics suppliers in the

'phone directory. Those white plastic kitchen chopping boards would

probably work in a pinch. Other options include Lignum Vitae (the natural

equivalent of UHMW, self lubricating oily hardwood, now a scarce

resource); A sheet material made from cloth laminated with phenolic resin

by Micarta (and other companies); Commercially manufactured sheaves in

plastic or bronze.

Pin: Brass rod can be obtained from the hardware store.

Quarter inch diameter is easy to find, and conveniently compatible with a

number of small commercially made sheaves. Brass is tougher than the

plastic sheave yet still easy to cut and finish. Stainless rod is almost

as easy to find, and corrosion resistant, at the cost of more hacksaw

effort.

Strop: Three strand rope is what's needed - making grommets

from modern braided line is a rather specialised activity. If you really

really want to go that way I'd point you in the direction of

Brion Toss Yacht Rigging in Port

Townsend - they run courses and sell instructional materials.

Natural fibre rope is difficult to find in small sizes of good

quality. Most of what is available is Sisal or Manila, of dubious

manufacture.

That leaves us with synthetics. Dacron is the obvious choice - it is

resistant to the marine environment, holds up well to UV radiation,

stretches very little, and is fairly readily available from sailmakers

suppliers

or chandlers. Nylon 3 strand could work, although it is stretchy. An ideal

strop stretches not at all, since excessive stretch could allow the shell

of the block to pop out of the loop of the strop under strain. Most

polypropylene breaks down rather quickly from UV damage, although there

are UV stabilised products out there if you can find them.

Riveting: Silicon Bronze ring nails are one possibility.

These are tough enough to do the job, but not so tough that they'll

destroy a carbide tip if you accidentally hit one with a router or saw.

Another option is copper nails and roves. I've seen blocks assembled with

threaded brass rod run through pre-drilled holes - if I was trying that

I'd run a steel rod through first to chase a thread.

Glue: Probably most Type II waterproof adhesives would work

adequately. I use ProBond polyurethane and the resulting glue lines are

stronger than the timber, even on fairly oily woods. If I was mixing epoxy

for another job I might use that instead.

The tools:

If you have patience, these blocks require hardly any tools - a

practical minimum would be; drill, hand saw(s), rasps (round, flat),

clamps and sandpaper. In the method explained below, I'll describe what I

used and suggest alternatives. If you have access to any of the following

they'll speed things up, but none of the fancy stuff is strictly

necessary.

Router with roundover and corebox bits

Bandsaw

Tablesaw

Drill or drill press with bits and holesaw

Microplane rasps

Belt sander

The method:

They're your blocks - the dimensions of the various parts are

inter-related, but they are up to you.

Start by deciding your sheave size: What size of line will the block

be turning? What size of sheave material is easily available? If sheave

making turns out to be less fun than you expected, can you get a

substitute commercial sheave which will fit? (amongst others, Harken and

Ronstan both list

sheaves). If you think you are likely to go the commercial sheave route, I

suggest obtaining some sample sheaves before you make the block shells -

dimensions in catalogues can be distressingly 'approximate'.

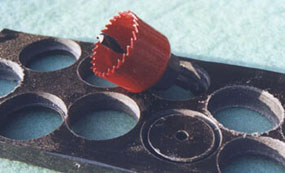

Your

sheave stock should be a bit thicker than the diameter of line you will be

using, to leave a 'rim' around the periphery of the sheave. Quarter inch

(6.5mm) diameter line suggests 5/16" sheave stock, but 3/8" will work

fine, and even half inch won't look too terrible. Within reason, a larger

diameter sheave will turn more easily. Most hole saw mandrels use quarter

inch pilot drills. Once you have a pile of sheave blanks cut out you might

want to run a 17/64ths drill through the centre holes to ensure they spin

freely on the quarter inch pin. Your

sheave stock should be a bit thicker than the diameter of line you will be

using, to leave a 'rim' around the periphery of the sheave. Quarter inch

(6.5mm) diameter line suggests 5/16" sheave stock, but 3/8" will work

fine, and even half inch won't look too terrible. Within reason, a larger

diameter sheave will turn more easily. Most hole saw mandrels use quarter

inch pilot drills. Once you have a pile of sheave blanks cut out you might

want to run a 17/64ths drill through the centre holes to ensure they spin

freely on the quarter inch pin.

Sheaves,

before and after. The finished ones are inch and an eighth in diameter. Sheaves,

before and after. The finished ones are inch and an eighth in diameter.

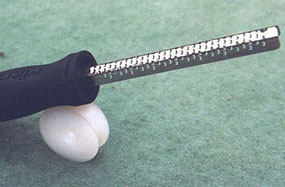

With the head sawn off, a 1/4 inch bolt makes a simple mandrel for

turning the groove into the sheaves. Once mounted in the chuck of a drill

press (or of a well-clamped down power drill), the wing nut on the mandrel

allows the finished sheave to be exchanged for another blank - the process

of cutting the groove doesn't take long.

For

cutting the grooves, I use a small round

Microplane

rasp - these things are great. A bit like razor sharp cheese graters, they

cut where rasps abrade, leaving smooth finish. With the blank turning

slowly, gently present the rasp to the edge of the blank. A very slight

rolling movement of the rasp will produce huge volumes of paper-thin

plastic shavings, and in no time you will be on to the next sheave. For

cutting the grooves, I use a small round

Microplane

rasp - these things are great. A bit like razor sharp cheese graters, they

cut where rasps abrade, leaving smooth finish. With the blank turning

slowly, gently present the rasp to the edge of the blank. A very slight

rolling movement of the rasp will produce huge volumes of paper-thin

plastic shavings, and in no time you will be on to the next sheave.

Turning directly on the pin, UHMW plastic sheaves spin quite freely.

If you anticipate heavy loads, Oil impregnated sintered bronze bushings

are available in convenient sizes. After opening out the hole in the

centre of the sheave to half an inch diameter or more, it is easy to press

in a sleeve. Try your local bearing shop.

Now the woodwork starts: You are going to make four strips - two big

ones for the sides of the block (the 'cheeks') and two strips to form the

top and bottom of the 'middle third'. The four strips will all be the same

length. How long? How many blocks are you making? Multiply the number of

blocks by the width of the cheeks to get the overall length. Don't forget

to allow for the saw kerf you will lose when you sever the blocks from the

mother-strip.

Add 1/16" clearance to the measured thickness of your sheave

material, and rip to width the strips for the top and bottom of the centre

section. Watch grain alignment here.

Optionally, cut the top strip deeper, and rout a cove inside face of

top

Rip both centre section strips to height.

Cut cheek strips, checking that the long axis of the block falls

cross-grain - the simplest way to get this right is to imagine you were

going to use a hatchet to split the wood for kindling - you want to make

sure that the strain on the pin is not in the same direction as your

hatchet blow would fall.

Align

the strips, glue and clamp. If you are doing lots of these glue-ups, it

might be worth making a spacer strip from UHMW or another 'unglue-able'

plastic. The spacer strip fits into the glueup in the space which will

later be occupied by the sheaves, and makes alignment a breeze. Align

the strips, glue and clamp. If you are doing lots of these glue-ups, it

might be worth making a spacer strip from UHMW or another 'unglue-able'

plastic. The spacer strip fits into the glueup in the space which will

later be occupied by the sheaves, and makes alignment a breeze.

Once the glue has set, clean up the squeeze-out. Next, saw block

sized chunks off the assembled strips. Excess glue inside the shells

blanks can be cleaned up at this stage with a chisel or scraper.

Next, drill for pin and rivets. If you have a drill press, a simple

jig will speed up this process, and assure a degree of uniformity. All

that I use is a piece of scrap ply with two scrap wood 'fences' pinned on

to it at right angles.

The

fences hold the block-to-be in the right position for the centre (pin)

hole to fall under the bit. Make sure you know which end of your

block-blank is the top - the pin hole is not usually in the centre of the

shell! If you will be riveting your shells drill all your pin-holes first.

Next, reposition the jig placing the riveting hole locations under the

bit. Turn the shell over, and end for end, to drill the four rivet holes.

In the absence of a drill press this can all be done with a hand drill,

but take care to ensure that the pin hole is absolutely square to the

block. Any major misalignment of the pin will result in a block inclined

to jam its sheave. If things get really squint you might not even be able

to fit the sheave. The

fences hold the block-to-be in the right position for the centre (pin)

hole to fall under the bit. Make sure you know which end of your

block-blank is the top - the pin hole is not usually in the centre of the

shell! If you will be riveting your shells drill all your pin-holes first.

Next, reposition the jig placing the riveting hole locations under the

bit. Turn the shell over, and end for end, to drill the four rivet holes.

In the absence of a drill press this can all be done with a hand drill,

but take care to ensure that the pin hole is absolutely square to the

block. Any major misalignment of the pin will result in a block inclined

to jam its sheave. If things get really squint you might not even be able

to fit the sheave.

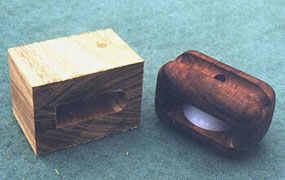

It

doesn't take long to get from a blank to a finished shell. Top right is a

blank with the groove machined for the rope strop. Top left is the same

size of blank having had its corners rounded over. Front centre is an

identical shell having been sanded to final shape, and with a first coat

of oil applied. It

doesn't take long to get from a blank to a finished shell. Top right is a

blank with the groove machined for the rope strop. Top left is the same

size of blank having had its corners rounded over. Front centre is an

identical shell having been sanded to final shape, and with a first coat

of oil applied.

A table mounted router with a fence, turning a 'core box' bit will

make short work of cutting a cove along the long axis of the block. This

cove does not need to be very deep - its purpose is to provide a recess

for the rope strop. Even with small blocks, where the strop material may

be 3/8" or less, a half inch bit will work fine; just cut a shallower

cove.

If the router is not available, use the round rasp to cut a notch

into the block where each end of the cove would fall. This is the only

part of the recess which is really doing much work in keeping the strop

on. The old blocks were done that way, and

there is an argument to be made for leaving extra wood around the centre

of the shell, giving the pin more bury.

Changing the core box bit for a roundover, pass the shell across the

table every which way, removing all external corners. A bandsaw can help

here if the router isn't available, and can be used to give a pleasing

profile to wide cheeked blocks regardless. A coping saw will do a job,

though slowly. Otherwise, a few passes with the block plane followed by

some judicious rasping will bring you to the same place.

Using

a rasp, round the bottom of the score where the rope reeved through the

block might otherwise rub. This is easier to do than to describe. Using

a rasp, round the bottom of the score where the rope reeved through the

block might otherwise rub. This is easier to do than to describe.

The finished shape of the area needing attention can be seen in this

shell. Compare the shape of the finished shell with the routed blank shown

above.

If you have decided to rivet your

shells, this might be the time to do it. Particularly in dense hardwoods I

find it easier to drive the nails while the shell is still a square-sided

blank, but that commits you to cutting down the nails as you shape the

block.

Even

with generous pre-drilled holes, driving 8d bronze nails into oak proved

so trying that I ended up using the bench vise to press them into place.

Drive two nails from either side of the shell, on diagonals, so that both

ends of the shell have a nail through them in each direction. This shell

is white oak (although the oil finish looks red). Having been worked down

from square with hand tools, it shows the traditional form of the groove

to hold the strop. Even

with generous pre-drilled holes, driving 8d bronze nails into oak proved

so trying that I ended up using the bench vise to press them into place.

Drive two nails from either side of the shell, on diagonals, so that both

ends of the shell have a nail through them in each direction. This shell

is white oak (although the oil finish looks red). Having been worked down

from square with hand tools, it shows the traditional form of the groove

to hold the strop.

Using

a sharp chisel, clean up any excess glue inside the shell. Sand and finish

the wood to taste. I used UV stabilised Tung oil - I like oil finishes -

but spar varnish would work just fine. The quarter inch diameter brass or

stainless rod for the pin can now be cut to length and gently rounded at

the ends to remove burrs. Pin length will depend on your shell dimensions

- the pin should be just short enough to lie flush with the wood, allowing

the rope strop to settle in the cove. Using

a sharp chisel, clean up any excess glue inside the shell. Sand and finish

the wood to taste. I used UV stabilised Tung oil - I like oil finishes -

but spar varnish would work just fine. The quarter inch diameter brass or

stainless rod for the pin can now be cut to length and gently rounded at

the ends to remove burrs. Pin length will depend on your shell dimensions

- the pin should be just short enough to lie flush with the wood, allowing

the rope strop to settle in the cove.

Now you can assemble pin, sheave and shell, ready for the ropework.

Making the little rope doughnuts called grommets can be easy and

enjoyable, or it can be deeply frustrating. Any decent book on ropework or

marlinespike work will give details on making grommets. I'd recommend The

Complete Rigger's Apprentice by Brion Toss - much more than knots and

splices. Harder to find, but a great introduction to rope work is Floris

Hin's 'The colour book of Knots'.

If you have never before made grommets from three strand rope I

would suggest getting hold of a few feet of manila - when unwound, each of

the strands retains the spiral shape it had when part of the rope - it

'holds its lay' - which makes it gratifyingly easy to lay up into a

grommet. Make a few to get the hang of things, then keep them around to

remind yourself that you can do it. You can always use them as

quoits.

Both Dacron and Nylon are very soft when unlaid, and can be

frustrating 'grommetees' One solution is to use a 'clue', laying the

grommet strand into the place of each of the three strands in turn.

Another possibility is to use a temporary stiffening agent to help the

Dacron hold its lay. I've used cheap hair gel with considerable success

for this purpose (what else would I use it for?).

In the interests of completeness, here's a basic version of grommet

making instructions....

First, work out what length of rope you need. Pass the rope round

the shell of the block, and add an allowance for the thimble eye. Take the

resulting measurement, and multiply it by four. Cut your rope to length,

and whip or tape the ends of the three strands to prevent them unravelling.

Second,

gently unwind one of the three strands from around the other two.

Synthetic rope repays gentleness - the less you manhandle the strand the

better it will retain the spiral shape it had while part of the rope. Second,

gently unwind one of the three strands from around the other two.

Synthetic rope repays gentleness - the less you manhandle the strand the

better it will retain the spiral shape it had while part of the rope.

Now, take the single strand and starting in the middle, lay it back

against itself to form a loop of the 'block and eye' dimension you

originally measured. Carefully wrap the strand around itself, re-creating

the spiral form of the original rope.

Working

out towards each end you will eventually have a three strand loop of rope,

with two single strand tails. That's your grommet. Working

out towards each end you will eventually have a three strand loop of rope,

with two single strand tails. That's your grommet.

Finishing a grommet is done like a long splice - Split each tail

into two bundles of yarns. Tie one half of each tail together in an

overhand knot and pull it tight enough to drop the half-strands down into

the middle of the rope. Work the other halves into the rope over one

strand then under the next, and so on.

Other stropping options include webbing of the sort used for

mountaineering equipment, and making 'selvagees' - essentially multiple

loops of thinner cord such as small braid. The Ashley Book of Knots covers

stropping variants in some detail.

This

strop has no thimble; Instead, the eye has been served over with heavy

waxed twine. Once the size of the eye has been established, and before the

strop is closed round the block, a tight spiral winding of twine is worked

around the portion of the rope which will form the eye. The ends of the

twine can be finished by tucking then under the last few turns, or by

stitching through with a sail needle. This

strop has no thimble; Instead, the eye has been served over with heavy

waxed twine. Once the size of the eye has been established, and before the

strop is closed round the block, a tight spiral winding of twine is worked

around the portion of the rope which will form the eye. The ends of the

twine can be finished by tucking then under the last few turns, or by

stitching through with a sail needle.

Closing

the grommet around the shell of the block is done by with a seizing. Place

the rope around the shell and start the seizing about two rope diameters

above the top of the block - the seizing is worked towards the block,

drawing the rope together and pinching the shell in place. Closing

the grommet around the shell of the block is done by with a seizing. Place

the rope around the shell and start the seizing about two rope diameters

above the top of the block - the seizing is worked towards the block,

drawing the rope together and pinching the shell in place.

This is a racking seizing, with the twine left loose to show more

clearly the 'over and under' figure eight path taken.

In

a real seizing, each turn of the twine is pulled up tight before the next

is put in. If you have never seized rope together before, be prepared to

be surprised as to just how much strength a little bit of twine can add to

the whole. The sample in the pictures is manila seized with tarred hemp,

and it gets very rigid by the end of the process. In

a real seizing, each turn of the twine is pulled up tight before the next

is put in. If you have never seized rope together before, be prepared to

be surprised as to just how much strength a little bit of twine can add to

the whole. The sample in the pictures is manila seized with tarred hemp,

and it gets very rigid by the end of the process.

Once

the racking turns are completed, work your way back down (up?) the seizing

, wrapping a second layer of twine over the first, with each turn sitting

in the groove between turns on the first layer. Unlike the racking turns,

these 'riding turns' do not weave in and out between the two ropes.

Instead, they are simply wrapped round the whole bundle. They do not need

to be hauled as tight as the racking turns - hand tight is fine. Once

the racking turns are completed, work your way back down (up?) the seizing

, wrapping a second layer of twine over the first, with each turn sitting

in the groove between turns on the first layer. Unlike the racking turns,

these 'riding turns' do not weave in and out between the two ropes.

Instead, they are simply wrapped round the whole bundle. They do not need

to be hauled as tight as the racking turns - hand tight is fine.

For the size of rope shown, this seizing is a bit short. Ideally the

finished seizing should be about as long as it is wide.

With

the racking and riding turns in place, a couple of frapping turns are

taken around the seizing, between the ropes as shown. To finish off, the

start and end of the twine can be square knotted together. Since I often

bury the start of the twine, I usually finish off by leading the end of

the twine round the frapping in a spiral, drawing all tight before cutting

off the tail. With

the racking and riding turns in place, a couple of frapping turns are

taken around the seizing, between the ropes as shown. To finish off, the

start and end of the twine can be square knotted together. Since I often

bury the start of the twine, I usually finish off by leading the end of

the twine round the frapping in a spiral, drawing all tight before cutting

off the tail.

Galvanised or stainless thimbles can be found anywhere that sells

wire rope - most big hardware stores. Seized into the grommet above the

block they provide a hard point to connect a

shackle. With a larger grommet, a second thimble can be seized in at the

bottom end of the block to receive the standing part in a purchase.

For

a block which will be attached to a spar, a longer version of the becket

shown here can be worked up, then seized around the shell in place of the

grommet. The knob and eye at the top of the block pass around the spar,

allowing the block to be 'buttoned' in place. For

a block which will be attached to a spar, a longer version of the becket

shown here can be worked up, then seized around the shell in place of the

grommet. The knob and eye at the top of the block pass around the spar,

allowing the block to be 'buttoned' in place.

Another grommet-free method is to work an eyesplice into the end of

a line. Passing round the shell of the block instead of the grommet, the

eye is seized into place.

Instead

of using thimbles and shackles to attach this block, a small wooden toggle

has been seized into the end of a line. Using a served-over soft eye

formed from the strop, the block can be buttoned onto the end of the line.

Low-tech, but effective. Instead

of using thimbles and shackles to attach this block, a small wooden toggle

has been seized into the end of a line. Using a served-over soft eye

formed from the strop, the block can be buttoned onto the end of the line.

Low-tech, but effective.

I've

had fun making these little blocks. They use so little material that I can

justify using woods normally beyond my pocket. I've

had fun making these little blocks. They use so little material that I can

justify using woods normally beyond my pocket.

The hand shaping can be done with a small rasp and a scrap of

sandpaper, allowing the work-in-progress to be carried around in a pocket.

Lunch-breaks can become boat-breaks. Enjoy! |