We were in the Florida Keys, getting ready to go kayaking when we heard Phil Bolger had died.

Our friend, Noel Davis, called on the cell phone in the morning to let us know. It was two days after the event, and word had filtered out in the boating community. We were camping, without Internet access or even newspapers, and Noel figured I would want to know. I had recorded an interview with Phil and his wife, Susanne Altenburger, last October that Noel had run on his podcast, furledsails.com, earlier this year.

The natural reaction was to think back over our sporadic acquaintance of a quarter century. I first heard of Bolger in 1980, when his third book, Different Boats, was published. I saw a blurb for it somewhere and noted that it included buildable plans for a small dinghy. I had a 24-foot sloop at the time and wanted a dinghy, so I ordered the book.

What a revelation. I actually did build a Tortoise, the 6-foot, 6-inch dinghy that is the first design in the book, but the rest of that volume kept me fascinated. (Bolger certainly gave his permission for such diversions. In the forward to that book he observed, “Imaginary boats are almost as much fun as real ones, and much cheaper for all concerned.”)

First there was the writing itself. Bolger had an easy style, unlabored and direct. He had the knack for clear explanations of complex concepts and ideas while mixing in some humor and anecdotes along the way. And he was, as he put it, as honest as possible about the shortcomings of his work. As someone who makes a living out of assembling words in a hopefully readable order, it can be frustrating to see a “nonprofessional” writer like Phil do it better and apparently so effortlessly.

Then there were the designs! Up to that point, I had owned a Sunfish and the 24-foot sloop. I had never seen and barely heard of a leeboard. Unstayed rigs were something for dinghies, but even then they should be Bermudan with vangs, outhauls, cunninghams, and other various adjustments. Or so it was in my world. Bolger simply blew that world up. Here were sharpies, leeboards attached with ropes, large boats with unstayed Chinese lug sails, gaffers, sprit sails and hardly a stay or shroud to be found. Romp (still one of my favorites) drew a meager 18 inches with the centerboard up, and was ocean capable – an unimaginable concept in a world that thought only in terms of deep draft for ocean going and racing boats alike, the deeper the better.

Over the years I’ve poured over the book so many times, the binding has disintegrated. And before long, I also got his first two books, Small Boats and The Folding Schooner and Other Adventures in Boat Design. When 30-Odd Boats came out in 1982, I got that, too. (It’s binding is also largely gone.)

By then, another project was looming for me. Always fascinated with the OSTAR (single-handed trans-Atlantic) race, I was interested in a boat for the under-30-foot class. I had narrowed it to a couple options, either a Jay Benford dory or something designed by Bolger. Around 1983 or early 1984, I sent Bolger a letter, but didn’t hear back. A few months passed and I was moving toward the Benford dory but decided to send another letter to Gloucester, Bolger’s home for most of his life. There was a quick reply. Bolger was indeed interested in my project, but had lost my address from the first letter – he asked me to be a bit more redundant with it in future correspondence.

The agreed design price was very modest. It was obvious he had much more lucrative work on the drafting board, but he still fit my project in. His concept was roughly a double-sized version of his Gypsy daysailer, a good performer that would be easy to build, with a spartan interior that would keep building time and costs down. Our correspondence was pleasant and I remember, after making the initial down payment, sending the second installment early after being pleased with one of the initial cartoons. That earned me a mild admonishment not to prepay, as Bolger said he didn’t like “working off a dead horse.”

After a few months, the plans were finished and Bolger waived the last payment, saying the design had come together faster than expected, but the payment could be made if I won my class in the OSTAR. (Alas, because of family considerations, I never got to make the race.)

I wasn’t able to immediately begin construction, so I built his Zephyr design in the meantime, to sail in the shoal waters in the north Florida Gulf Coast. Fast to build and easy to set up and sail, the boat sampled shallow waters at her Gulf home but also as far away as the Florida Keys. It always amazed me that despite the narrow beam, I never flipped the boat and it provided a maximum amount of enjoyment for the hours invested in construction and upkeep.

|

Zephyr: A long, lean daysailer, quick to construct and satisfying to sail. |

| The lateen rig is quick to set up and well suited to the boat; it even has a reef. |

|

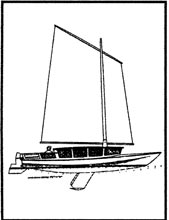

Work on the OSTAR boat, designed at 29 feet 10 inches by 7 feet 10 inches, began in early 1986 and was completed a year later. Some time was saved by ordering prescarfed plywood long enough to cut the panels for the tack and tape hull, but Bolger’s sensibilities and craft showed in the building time. The hull took 100 to 120 hours to build, with some part time help, and the entire boat, including making the spars, took between 4-500 hours. Yes it was spartan, but that’s still a fraction of the time it would take to build a similar craft by any other method.

|

A Bolger original, a 30-foot tack and tape boat, fast to build and ocean capable. |

| A hull that built in a little over 100 hours. |

|

|

The original cabin and keel, long and lean. Not much underwater to slow her down. |

We had some nice post construction correspondence about inevitable changes. The original 7 foot fin keel (yes, Bolger was known for shoal draft boats but in this case he decided a fixed deep draft was best for the purpose) was reduced to 5.5 feet in recognition of the boat’s home waters. And the initial dipping lug rig, which was beautiful to sail, was changed to a balanced lug to reduce the rigors of tacking and gybing on a 95-degree Gulf summer day. But the boat performed as hoped, swift and sure, and easy to handle, especially as a balanced lugger.

In 1992, my then wife decided as a present to arrange a visit with Bolger, which must have led to some funny moments as she tended to do things last minute and by phone, and Bolger notoriously was reluctant to use the phone. I’m not sure he had one at the time. Anyway, to my surprise, he agreed to host me on his 48-foot Resolution, on which he was then living, for a weekend that summer.

And what a visit! The conversation never stopped, unless we were asleep or out on boats. The topics included not only boats and their design, but politics, journalism, ancient Greek history, fantasy novels, architecture, airplanes, and dozens of other topics. One subject would suggest another and off we go, ricocheting from one topic to the next. He also mentioned Susanne Altenburger, who he had recently met, but I didn’t get to meet her, that time. Perhaps my lasting impression of the trip was how keen an observer Bolger was, not only of things nautical but of people, politics (he was a libertarian), society, and the things around him. You might not agree with his opinion on something, but there was no question any opinion he offered had been thoroughly thought out and was based on his careful observations.

| Resolution at the Montgomery yard around 1992; beside it is Kotick, the Bolger's kayak built for him by Dynamite Payson. |

|

A high point was a trip out into the waters of Gloucester, which Bolger knew as intimately as an ardent gardener knows his back yard. He was in Kotick, his Dynamite Payson-built kayak and I was in Sweet Pea, which Bolger had recently designed as a rowing/sailing boat. I had only rowed wide, heavy flat bottom metal boats in public parks, or my own Zephyr, a good sailor but an indifferent rower. But Sweet Pea responded to strokes of the oar in ways I never imagined, showing me that rowing could be fun, not a chore. I was entranced, but Bolger later told me he didn’t consider Sweet Pea that good of an oar-powered craft. I remember his scooting ahead as a mild powerboat wake came our way, so he could study how Sweet Pea’s bow went through it.

At some point during the visit, I either saw his Spur II design, or knew he had drawn it and that Dave Montgomery (Resolution was at the Montgomery yard), was going to build one. Not long after I returned home, I conceived the somewhat audacious scheme of borrowing Spur II the following year and rowing in the Blackburn Challenge – the 20-plus mile circumnavigation of Cape Ann Island, the location of Gloucester. If I couldn’t do an OSTAR, at least here was an achievable adventure. Bolger graciously assented to my proposal, gracious particularly because he knew of my near total lack of rowing experience. Training was on a rowing machine and some in the Zephyr.

That 1993 visit was notable for a number of reasons. One was our conversation picked up like we had left off the previous day instead of the previous year. Second was the rowing prowess of the Spur II, which far surpassed my feeble skills. The wind had blown 15-20 for days leading up to the challenge, easing to 10-15 the day of the event, which still made for some choppy seas. The Spur II simply soared over the waves, propelling easily and taking no more than a few drops of spray for the entire course. In running terms, I completed the course at a brisk walk; if I had been in better shape I might have been able to do a slow run. But the time was respectable, a tribute to the design, not the skipper that day.

The third thrill of the trip was taking the prototype Spartina out for a sail. Intended to replace a catboat built at the Montgomery yard since the 20s, it was a lapstrake ply construction, with a centerboard, a sliding gunter sail (gaff sloop optional) and absolutely hypnotic lines. This design will be periodically rediscovered as a Bolger classic in the coming years. Less than 16 feet long, you could stand on the gunnel without it dipping into the water and it had the most precise handling of any small boat I had been on. Easy on course, it would tack on a dime and maintain its momentum. (At the time, I was part way through construction of another Bolger boat, a v-bottom catboat that could be built at 15.5 feet or four feet longer. I built the longer version and it turned out to have Spartina’s qualities. The construction, done in fits and starts, was too haphazard for longevity, but we plan to rebuild the boat with a Birdwatcher cabin.)

The fourth discovery was Susanne, who came up for a visit while I was there. She took me out on the Spartina, and waited until the bow nearly hit the reeds on shore before tacking, sure of her knowledge of both the boat and the water. Bolger made no attempt to hide his deep affection for her.

Powerboats were not left out of this trip; Bolger and Susanne retrieved me from the Blackburn finish line in the prototype Hawkeye and I got a ride on the Shivaree, with Bolger directing my attention to the clean way the bow cut through the waves and the modest power needed to drive the boat.

It was sometime after this trip that it occurred to me many people did not fully understand much of Bolger’s work. His designs would be referred to as simple or simplified, especially smaller craft intended for homebuilders. But I don’t think simplicity was his goal, efficiency was – the best boat for the purpose with the least outlay of materials, time and effort. Zephyr can be built with about 24 hours labor (plus another 24 to sand and paint her) and is intended for someone who wants a boat that will take one to four (or more if some are small) with decent performance and not present a carpentry challenge to construct. My 30-footer got a deep draft because that was the best answer for open ocean speed. It got a lug rig because it avoided the expense and complexities of a stayed rig where one minor component failure brings down the mast. Many of his other large boats have shoal draft with leeboards or centerboards and fold-down rigs because they can explore close to shore, take berths or anchorages denied to deeper draft boats, and the simple rig reduces maintenance and costs. Over 90 percent of the boats in a marina don’t need the highly stressed stayed rigs to get the nth degree of performance to windward, so why put up with its complications and expense? Similarly, many of his power boats need smaller motors and hence less fuel than similarly sized craft. There was an underlying question here posed to a society based on excess: Why waste? That may have put Bolger out of step with much of the contemporary boating community, but I think it qualifies, in this time of diminishing resources, as visionary.

My next visit was in October 1999, when work took me to Boston. I visited Phil and Susanne, now married and operating Phil Bolger & Friends, for lunch and an afternoon’s conversation. Again, it picked up as though there had been no interruption from 1993 and covered a variety of topics. But it was as I was getting ready to leave that I saw the brilliance of their synergy. I casually mentioned that I still enjoyed sailing the 30-footer Phil designed for me, but its use was constricted, since I never got to use it in an OSTAR. The draft was really too deep to be practical for the Gulf, the cabin too cramped, a footwell would be nice in the flush-decked cockpit, and it would be pleasant to be able to fold down the mast for maintenance, instead of needing a crane in the yard to pull it. They pulled out their copy of the plans and an incredible 15 minutes outlined how the boat could be changed – a pivoting keel, like a giant centerboard, could be retrofitted. A tabernacle for the mast would be easy. The cabin could be raised and extended, including large hatches in the top for improved ventilation. The cockpit would get a footwell and a better arrangement for the outboard.

|

The modifications for design #459 showed the creativity of the Phil Bolger/Susanne Altenburger partnership. The details aren't great in this drawing, but note the swinging wing keel, where the wings pivot as the keel lifts up. A bar through the middle of the free flooding keel controls the wings. |

| The redesigned #459, Le Dulci-Mer, Moving right along close hauled in a fresh breeze. |

|

The resulting keel deserves particular mention. It wound up being a wing keel (actually a prototype for the Insolent 60 design) where the wings cantilever to remain parallel to the bottom as the keel pivots up to reduce draft. This was accomplished by making the steel fin keel free-flooding down the middle and running a rod through it to control the angle of the wings. It’s harder to describe than do, the drawing made it all clear, and a brilliant innovation. Bolger later told me that most of the changes came from Susanne.

My last visit was only a few months ago, again when work took me to Boston and I wrote to ask about a visit. To my surprise, Phil telephoned to invite me to spend a night. I gladly accepted. Once again the visit was marked by great conversation. As had gotten to be our custom, I took Phil and Susanne to dinner, and we preceded that by walking the Gloucester waterfront, looking at the boats. Much of our talk dealt with their fisheries project, a series of fuel efficient boats aimed at dealing with the combined problem of managed fish supplies and high fuel costs. The boats are aimed at allowing fishermen to make a living with smaller catches by reducing their fuel costs, and coincidentally, their engine and maintenance costs. The idea has been slow to catch on, but shows signs of recognition. Bolger, I think, had spent a lifetime refining his gift of seeing to the center of a problem and coming up with simple, elegant solutions and it was hard for him to understand that other people didn’t have the same talent for stripping away the superfluous.

I recorded a one hour, 40 minute interview, which Noel turned into two shows (Part 1 & Part 2) for his podcast. This was just before his 81st birthday, and during the visit and the interview, he struck me as fully mentally alert as any of my earlier visits, although physically he seemed a little frailer. Suzanne mentioned he had been ill several months before and doctors thought it might have been a stroke before finally diagnosing Lyme disease. And Phil mentioned the strain of keeping up with his correspondence, noting he was doing so now but there was a backlog that would never be answered. He and Susanne also said that they were working to finish three designs, two advance sharpies and the Insolent 60, but beyond that he was not taking any new design work, although there were some books they were planning. They were, of course, still offering designs from his extensive catalog for sale.

It’s frustrating to try to capture someone as intelligent, accomplished, and complex as Phil Bolger in a few hundred words, or even a few thousand, and a handful of anecdotes and remembrances. But some things he said about other people seem also fitting for him.

When builder and designer Thomas Firth Jones passed away recently, Bolger commented that he did all his own thinking. That’s a great description of Bolger as well. He was not one to listen to talking heads and follow their opinions. He did his own research and observation, and reached his own conclusions, not just about boats but any topic that engaged his interest. And that truly was a broad spectrum.

He also once wrote about Dynamite Payson, saying he had a pet theory that the stability of a society depended on a certain number of people with his type of sensibility and when it went below a certain threshold, that society deteriorated. I reminded him of that during the October interview, and he went on to add that Dynamite was a fine example of civilization. Both of those observations apply to Phil Bolger as well. As an astute observer, his conclusions, not just about boats, but a wide range of issues, were enlightening and added knowledge, not heat, to any discussion. And he was certainly a fine example of civilization. Most of us knew him as an incredibly creative and wide ranging boat designer – the Birdwatcher, Dovekies, power and sail step sharpies, the Instant Boats, incredibly beautiful yachts of all sizes, the humble and capable June Bug. But Bolger was also an accomplished writer and an original thinker, about things nautical and non-nautical, who put his ideas into practice. You can’t ask much more of a civilization than that.

When Noel hung up, I sat for a while, not knowing what to think. You can read Susanne’s account of Bolger’s death elsewhere here on Duckworks. Having known him, I felt compelled to respect his decision and felt mostly sad that Susanne will now have to do without his companionship.

We had planned to go kayaking and that's what we wound up doing: three short trips over the day. We poked closed to mangroves, looked through the roots to see how far back the water went, marveled at birds in the trees, and visited a sandbar at low tide, finding a live lightning whelk and laughing at the sea urchins, which adorn themselves with hats of castoff shells. Such poking was the kind of thing Phil Bolger liked people to do with boats, and that seemed a fitting homage.

***** |